Climate Change and the Right to Water

Take yourself on a trip back in time. Go to Mar del Plata, Argentina, in the year 1977. A high profile international conference is taking place under the auspices of the United Nations, full of hope and burdened with lofty aims. In that year, only 20% of the world's rural population in developing countries had access to safe drinking water.

At the conference, the world is relatively united around the importance of providing safe drinking water to the world's population, not only for its own sake, but also because 80% of all common diseases known to the world are water borne, and improving access to safe water will significantly boost global health and economic productivity. As a result of the Mar Del Plata declaration, the International Drinking Water Supply and Sanitation decade is announced, which intends to provide safe water and sanitation for everyone by 1990.

Zipping through time, let us go to 1990. An incredible 1.2 billion people have been provided with drinking water and 770 million people have been provided with sanitation. These achievements are being celebrated, but it is also recognised that population growth is proceeding at such a rate that this has not had much effect on the number of people without drinking water or sanitation. The global coverage rate of water services for instance increased from 75% in 1980 to 85% in 1990. However, many of the services provided during this period have broken down or are breaking down. Researchers are in the process of demonstrating that connecting a tap is not the same as having a service: investing in the people who manage a service, collect funds and maintain systems is crucially important. Internationally, commitment is being made to provide 'some for all' rather than 'all for some'.

Let's try again. Go to 2000, to the Millennium Declaration. More than 147 countries have agreed to commit to halving the number of people without access to safe water and sanitation by 2015. Clearly, the goals being set are much more sober than they were in 1977. At least the machine is up and running again and water and sanitation services are being delivered. But by now, it is becoming clear that neither states nor donors are making much progress in actually reaching the poor. 2.4 billion people still do not have access to adequate sanitation, and 1.2 billion do not have access to safe drinking water. Where services are provided, it is the low hanging fruit that is prioritised: periurban areas and small towns where people are easily reached help to boost the statistics that donors and states collect about their own progress. Also, it is emerging that the water sector is highly corrupt, and that funds are locked into all manner of complex bureaucratic processes but do not flow down to the local level where they are needed.

What is needed is non-discrimination, transparency and accountability on public and donor spending, so that those for whom the funds are intended have a say about how money is being spent and can participate in the planning of projects which are intended for no one other than themselves.

By 2002, this process has started to move. The International Committee on Economic Social and Cultural Rights has ruled that the right to life, which is a universal human right, includes the right to water. From this moment on, one country after another is officially recognising the right to water and takes steps to introduce the principles of non-discrimination, transparency, accountability and participation into national law. This is a huge step forward for civil society, as it is possible to push not only for pro-poor spending, but also to give the poor a voice in the shaping, monitoring and investigating of programmes developed on their behalf.

In 2009, a new problem is emerging. Climate change and widespread environmental destruction is unravelling the stability of the water cycle, resulting in regular droughts in some areas and excessive flooding in others. Plantation economies geared towards the export of water hungry crops to the rich west are claiming huge amounts of water for irrigation and polluting groundwater with pesticides. The security of access to water is being threatened from a new quarter, which is the fundamental way in which we interact with nature itself. Therefore, in the run up to Copenhagen, Both ENDs and its partners are lobbying for climate change to be included in the right to water. In every catchment area, enough water should be reserved to secure basic human needs, before the needs of the economy at large are satisfied, otherwise this would infringe on the basic human right to life. South Africa has already done this, and so has Indonesia. It is absolutely imperative that this concept of the basic needs reserve be written into the laws of all water scarce countries in order to protect the basic human right of human beings to water from being undermined from another direction.

For more information please contact our senior policy officer on the right to water and sanitation: Tobias Schmitz.

Photograph by: Hypergurl - Tanya

Read more about this subject

-

Blog / 15 April 2024

The year of truth: EU Member States urged to combat deforestation

The EU is the world's largest "importer of deforestation," due to the huge volumes of unsustainably produced soy, timber, palm oil, and other raw materials that EU member states import. After many years of delay, the European Parliament and the European Council passed a law in December 2023 to address this problem: The EU Deforestation Regulation (EUDR). Both ENDS is part of a broad coalition of organizations that have been pushing for this European legislation. However, there is now a serious delay, and perhaps even postponement, of the law's implementation. Objections have been raised by a number of member states, who are sensitive to lobbying by certain business sectors and producer countries.

-

News / 4 April 2024

EU ECA fossil fuel phase-out tracker reveals EU Member States’ lagging commitment to Paris Agreement goals in export credit policies

Our new report titled EU ECA fossil fuel phase-out tracker by Both ENDS, Counter Balance and Oil Change International sheds light on the concerning lack of harmony between EU Member States' export credit climate policies.

The report was updated on April 17th, following new responses by Member States on their respective policies.

-

Blog / 4 April 2024

If we women don't speak up, no one will speak for us

By Maaike Hendriks and Tamara Mohr

By Maaike Hendriks and Tamara MohrThis February women environmental defenders from around the world met each other in Indonesia. All these defenders face structural violence. GAGGA, the Global Alliance for Green and Gender Action, supports these women. This meeting in Indonesia provided a unique space for women, trans-, intersex and non-binary people who are often the subject of conversation but rarely have the opportunity to engage with each other and meet other defenders from around the world. For they are all amazingly knowledgeable, strong and resilient women whom we should take seriously.

-

News / 2 April 2024

The Climate lawsuit against Shell

Milieudefensie (Friends of the Earth Netherlands) and 6 other organisations are confidently heading into Shell’s appeal of the 2021 climate ruling, which will take place on April 2nd in The Hague. In the landmark lawsuit against the oil and gas company, the court decided that Shell must slash its CO2 emissions by 45%, in line with international climate agreements.

-

News / 29 March 2024

Both ENDS visit Tweede Kamer to talk about destructiveness of dredging worldwide

This week several Both ENDS colleagues visit Tweede Kamer der Staten-Generaal to meet Christine Teunissen and Luc Stultiens with partners from Mozambique, Indonesia and the Filippines to talk about the destructiveness of dredging worldwide and especially in projects with the aid of the Dutch government.

Read their plea

-

News / 27 March 2024

Changing of the guard: Paul Engel and Leida Rijnhout on the unique strength of Both ENDS

After eight years as chair of the Both ENDS Board, Paul Engel is now passing on the baton to Leida Rijnhout. In thus double interview, we look back and forwards with the outgoing and incoming chairs. Paul Engel sets the ball rolling on an enthusiastic note: “This organization decides itself what it is going to do, and does it very well. As the Board, we help and use our networks to provide support”. A conversation about taking the lead in systemic change and working with others around the world.

-

Press release / 25 March 2024

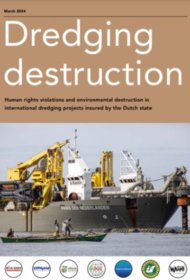

Dredging destruction; worldwide research into Dutch dredgers

Dredging Destruction: Report reveals how Dutch dredging companies are systematically destroying human lives and the environment around the world with the help of taxpayers’ money

The Netherlands is providing billions of euros in support for dredging projects by Boskalis and Van Oord around the world. All of these projects are destroying human lives and the environment. The Dutch government’s policy to protect people and planet is failing systemically. And after twelve years of studies and talking, there are no real improvements. It is time for a thorough clean-up of government support for the dredging sector.

-

Publication / 25 March 2024

-

News / 19 March 2024

Both ENDS - Remarkably Special

At Both ENDS, we hold our own responsibility, self-direction, an open feedback culture, and personal development in high regard. Chaos, you might think? Not at all, it leads to an effective way of working with much enjoyment. The flat organizational structure that Both ENDS has been implementing since 2016 is founded on collectivity. In this, you can also see our aim of 'Connecting people for change' reflected.

-

News / 12 March 2024

Equality as a key for international trade

Trade has been in the global spotlight once again in recent times. Recently, ministers from around the world gathered in Abu Dhabi at the WTO for negotiations on world trade in the coming years. However, participants from civil society were silenced. Never before has their freedom been so severely restricted at the WTO. In a time when geopolitical tensions are escalating by the day, it is crucial to prioritize equality in international trade. -

Event / 12 March 2024

From Policy To Practice: Funding Locally-led Gender-Just Climate Action

A discussion on the intersection of climate and gender justice - specifically on financing mechanisms for gender-just climate solutions!

-

News / 6 March 2024

Inspire inclusion at Women's day!

Happy Women's Day!

Friday March 8th we celebrate a gender equal world; free of stereotypes, bias, and discrimination. Around the world women are powers of change. We proudly present you; the voices of the next generation of environmental leaders of the JWH initiative. All our grantees are driving change in the environmental sector and have a strong say about the inclusive world.

-

News / 6 March 2024

Export Credit Agencies and development finance in the EU

We are seeing increased interest in the EU for blending different development financial instruments with export credits, even though export credits are not fit for this purpose. The European Commission is developing plans for using so-called export credits for financing everything from raw materials, to development projects, to weapons. A new report of Counter Balance is shedding light on the significant environmental and social impacts of projects financed by ECAs.

-

Press release / 4 March 2024

Dutch government calls for investigation into Malaysian timber certification

The Dutch government expects PEFC International to undertake an investigation into its own role as a forest certification system, using the Malaysian Timber Certification Scheme (MTCS). "It is about time the Dutch government takes a leading role in ensuring Malaysian timber entering The Netherlands is not associated with deforestation and human rights abuses," states Paul Wolvekamp of Both ENDS. "Considering that the Dutch government has the ambition to build 900.000 houses in the immediate future, involving massive volumes of timber, such as timber from Malaysia for window frames, builders, contractors, timber merchants and local governments rely on the Dutch government to have its, mandatory, timber procurement better organised, i.e. from reliable, accountable sources'.

-

Blog / 27 February 2024

Partners fighting for rights within natural resource exploration in Uganda

A recent visit to Uganda highlighted the country as the latest example of ethical, environmental and human rights dilemmas brought forth by natural resource exploration.

Under the guise of economic prosperity and energy security, the future of Uganda’s forests, lakes, national parks, and by extension that of the people that depend on these resources, is increasingly endangered. Both ENDS partners in Uganda work with local communities to preserve these natural environments and the livelihoods that come from it.

-

Blog / 26 February 2024

Brumadinho: 5 years without justice

On January 25, 2019, Brumadinho region witnessed a tragedy-crime that claimed 272 lives, including two unborn children, affectionately called "Jewels" in response to VALE’s declarations that the company, as a Brazilian jewel, should not be condemned for an accident. However, the investigations about B1 dam collapse, at Córrego do Feijão Mine, showed that the scar left on the community and environment was not an accident, but VALE negligence.

-

Blog / 26 February 2024

Exploring sustainable farming practices with partners in Indonesia

From land regeneration to improving soil health – trees play a crucial role in almost all our ecosystems. Agroforestry makes use of these benefits by combining agriculture and forestry. Agroforestry, and the reforestation and conservation efforts that are part of it, improves biodiversity and climate resilience, as well as the livelihoods of the farming communities involved.

-

Blog / 26 February 2024

Impacts of the fossil fuel sector in Guanabara Bay

Last September, together with our Brazilian partner FASE, Marius Troost of Both ENDS visited Guanabara Bay (near Rio de Janeiro) to map the impacts of the fossil fuel sector there. During the trip, he was struck by the braveness and fearlessness of the local fisherfolk who protest the injustices faced by the people who live around Guanabara Bay and about the damage done to the environment.

-

News / 14 February 2024

Petition to protect the Saamaka people and the Amazon Forest

The Saamaka People, the Afro-descendant tribe of Suriname, have preserved close to 1.4 million hectares of the Amazon rainforest. They have for decades urged the government to recognise their ancestral territorial land rights.

-

News / 8 February 2024

The litmus test for the devastating race track in Lombok

A race track for international motor bike events in Lombok continues to worry human rights experts around the world. Both ENDS and its partners are increasingly concerned about the project’s implications for ethical standards in global development financing going forward for it continues to hurt the most basic social and environmental safeguards.