Rights for people, rules for corporations: the case of Paraguay

Indigenous communities in Paraguay saw their attempts to regain their ancestral lands thwarted by German investors. This is the level of impact that investment treaties can have on social, environmental and economic development and rights. Why? Because of the ‘Investor-to-State Dispute Settlement’ (ISDS) clauses that are included in many such treaties.

Bilateral Investment Treaties (BITs ) often guarantee rights to land to foreign companies and individuals. This creates a major problem, especially when ISDS is included in the treaty. Even if the treaty is never actually invoked for arbitration, the mere existence of ISDS often serves as a threat to the authorities who intend to enact land distribution reforms. The reason is that ISDS enables foreigners to claim economic compensation for what they consider expropriation, based on the clauses on 'compensation' and 'legitimate expectations' of investment agreements. Compensation should be aligned with current full market prices and often involves expectations over future profits. This is the more ironic given that investors may well have acquired rights over the land far below the full market price in first place.

In 1994, the state of Paraguay recognised in its constitution that indigenous peoples had inhabited the country's territory prior to the arrival of colonisers in the 16th century and the subsequent formation of the nation state. This milestone recognition opened the possibility for the 19 different indigenous groups in Paraguay to make a legal claim for the restitution of land that over the past centuries had been taken away from them. The hope among the indigenous people was that this marked a new beginning. Indigenous leaders had made it very clear that the lack of indigenous land rights was "the foundation of the indigenous peoples' misery". However, ISDS soon smothered their hope. The mechanism was the reason why the government refused to fulfil its constitutional duty to return ancestral land to its traditional owners.

The Palmital case

In 1992, Paraguay adopted a new agrarian law, which stipulated that land that does not serve a social function must be sold by the owners or either it will be expropriated. 120 landless families living in the Palmital settlement, an idle estate of 1000 hectares owned by German citizens, used this new law to request a transfer of the land titles to them. The Paraguayan Senate, however, refused to grant its consent, arguing that expropriation of the land from its German owners would violate the country's 1993 BIT with Germany. Consequently, the police violently expelled the families from their settlement several times, but each time they returned to the estate. There are rumours that the German Embassy in Paraguay had referred to the BIT in the Palmital context, suggesting that expropriation of the land would be interpreted as a violation of the treaty. In the end the landless peasants, the German owners and the state of Paraguay reached an out of court settlement that allowed the families to stay on the land.

The Sawhoyamaxa case

In the early 1990s, leaders of the Sawhoyamaxa indigenous community started requesting the authorities in Paraguay for the restitution of their ancestral land, which had been taken away from them by foreigners in the late 19th century. The Sawhoyamaxa had used these lands to hunt and fish, to produce traditional medicines and to perform cultural rituals. Without land, the communities became marginalised. Many of them were forced to enter paid employment with the new farm owners, who subjected them to degrading work conditions. The community ended up living on the roadside.

Because the Paraguayan state failed to protect their rights, the Sawhoyamaxa brought their case to the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (ICHR), supported by the NGO Tierra Viva. The state of Paraguay had argued that since the owner of the disputed land was a German citizen, expropriation of the land would imply a breach of the BIT between Paraguay and Germany. On 29 March 2006, however, the ICHR dismissed this argument. It ruled that the Paraguayan state was effectively violating the Sawhoyamaxa's rights to life, property and judicial protection. It ordered the state to return the ancestral lands to the community within three years.

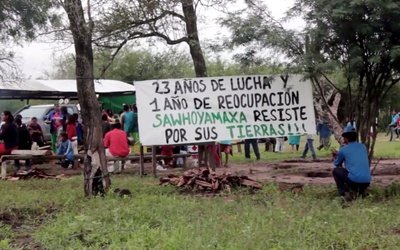

Paraguay failed to follow through on this obligation and years of legal tug-of-war and massive mobilisations ensued. Complaints were filed even at the Constitutional Chamber of the Supreme Court of Justice. In October 2014, the Supreme Court unanimously rejected the estate owners' claims that the decision to expropriate 14,404 hectares and give them back to Sawhoyamaxa was 'unconstitutional'. On hearing this ruling, the community leaders said: "We feel as if we were just released from prison". Yet there was concern that the Germans might use the German BIT with Paraguay to challenge this final decision of the national courts of Paraguay. Fortunately, this did not happen. In 2015, the Sawhoyamaxa communities finally received the titles to the land that for centuries had been their home.

This case was highlighted as part of the

'Rights for People, Rules for Corporations – Stop ISDS' campaign week of 14-18 October 2019

Background on the 'Rights for People, Rules for Corporations - Stop ISDS' campaign

More information:

Also see the case of Indonesia

For more information

Read more about this subject

-

Dossier

Investment treaties

Investment treaties must be inclusive, sustainable and fair. That means that they must not put the interests of companies before those of people and their living environment.

-

Publication / 30 October 2023

-

Dossier

Rights for People, Rules for Corporations – Stop ISDS!

Indigenous communities in Paraguay saw their attempts to regain their ancestral lands thwarted by German investors. In Indonesia, US-based mining companies succeeded to roll back new laws that were meant to boost the country’s economic development and protect its forests. This is the level of impact that investment treaties can have on social, environmental and economic development and rights. Why? Because of the ‘Investor-to-State Dispute Settlement’ clauses that are included in many such treaties.

-

Event / 22 February 2022, 16:00 - 17:30

Webinar and launch of new publication about EU-Mercosur

What is the EU-Mercosur association treaty and why is it controversial? What could be the implications of the treaty for people and their livelihoods both in EU and Mercosur countries? For more information about these and other issues, see our new publication and join our interactive webinar next week!

Register here

-

Press release / 23 May 2023

60th anniversary of Dutch bilateral investment treaties no cause for celebration

On 23 May, the Netherlands celebrates 60 years of bilateral investment treaties (BITs). The first BIT was signed with Tunisia in 1963. These treaties were intended to make an important contribution to protecting foreign investments by Dutch companies. A study by SOMO, Both ENDS and the Transnational Institute (TNI), however, shows that in practice they mainly give multinationals a powerful instrument that has far-reaching consequences people and the environment worldwide.

-

Publication / 23 May 2023

-

News / 11 October 2019

Rights for people, rules for corporations: the case of Indonesia

In Indonesia, US-based mining companies succeeded to roll back new laws that were meant to boost the country’s economic development and protect its forests. This is the level of impact that investment treaties can have on social, environmental and economic development and rights. Why? Because of the ‘Investor-to-State Dispute Settlement’ (ISDS) clauses that are included in many such treaties.

-

Publication / 15 February 2022

-

Dossier

Trade agreements

International trade agreements often have far-reaching consequences not only for the economy of a country, but also for people and the environment. It is primarily the most vulnerable groups who suffer most from these agreements.

-

Letter / 26 June 2020

Letter to governments over wave of Covid-19 claims in 'corporate courts'

Countries could be facing a wave of cases from transnational corporations suing governments over actions taken to respond to the Covid pandemic using a system known as investor-state dispute settlement, or ISDS. 630 organisations from across the world, representing hundreds of millions of people, are calling on governments in an open letter to urgently take action to shut down this threat.

-

Publication / 21 September 2015

-

Publication / 4 April 2019

-

News / 14 October 2016

5 alternative arguments against TTIP

Both ENDS will join the protest against trade treaties TTIP, CETA and TiSA on Saturday October 22nd in Amsterdam. These treaties will have negative impacts, not only in the Netherlands and Europe, but also - and maybe even more so - in developing countries.

-

News / 19 June 2018

NGO's send letter to Minister Kaag to call for termination of BIT with Burkina Faso

Today, Both ENDS sent a letter, signed by various civil society organisations, to Sigrid Kaag (Dutch Minister of Aid & Trade) reminding her of an important deadline and to urge her to terminate the Bilateral Investment Treaty (BIT) that exists between the Netherlands and Burkina Faso. The treaty, which can be very harmful for a poor country such as Burkina Faso, will automatically be renewed for the next 15 years if it is not terminated before July 1st this year.

-

Publication / 10 March 2016

-

News / 26 June 2020

630 civil society groups sound alarm over wave of Covid-19 claims in 'corporate courts'

Countries could be facing a wave of cases from transnational corporations suing governments over actions taken to respond to the Covid pandemic using a system known as investor-state dispute settlement, or ISDS. Cases could arise from actions that many governments have taken to save lives, stem the pandemic, protect jobs, counter economic disaster and ensure peoples' basic needs are met. Threats of cases have already been made in Peru over the suspension of charging on toll roads, and law firms are actively advising corporations of the options open to them. 630 organisations from across the world, representing hundreds of millions of people, are calling on governments in an open letter to urgently take action to shut down this threat. The letter below is published today.

-

Publication / 19 September 2016

-

Publication / 12 November 2020

-

Publication / 7 July 2022

-

News / 21 January 2019

Launch of European campaign against unfair investment agreements

Today an alliance of more than 150 organisations, trade unions and social movements in countries across Europe is launching a joint programme against unfair trade and investment agreements, and especially against the controversial Investor-to-State-Dispute-Settlement (ISDS) mechanism. Under ISDS, investors can bring complaints against states whose social and environmental legislation pose a threat to their profits.