Wanted: Brave people. Contemporary Palaver Supports Local Self-Government

Wanted: Brave people. Contemporary Palaver Supports Local Self-Government

Imagine well-informed people, who know how to present their ideas and opinions to others, who actually listen to each other, who balance all their interests and visions and make decisions together. Nobody wins the-winner-takes-all prize, and, meanwhile, everyone is reaching a compromise. Authorities who sponsor 'open day' activities explain how they govern their jurisdictions. For us in the West, this all doesn't sound so incredible - even though many things still go wrong here as well -but in many parts of the world, this is only a very distant ideal.

When she was dreaming her dreams of a transparent and democratic society, Awimbo deliberately referred back to the ancient African consultation model of the palaver, which is a kind of meeting that often takes place outdoors, in the shade of a tall tree like the baobab, where people keep on talking as long as necessary until everyone comes to an agreement. The palaver is not hindered by agendas and schedules. The palaver is a typical African method and reflects the African rhythm of life.

The palaver has not disappeared; it is still very alive in rural areas, although the related notion of self-governance has faded into the background. Since the colonial powers began their domination of Africa, the traditional chiefs - as the major consultants - came under government control long ago. Awimbo considers the palaver to be an expression of self-governance. "In a certain sense, I want to recuperate this traditional way of making decisions, with people governing themselves. It's a system that is quite understandable. The elders determined when the seeds were to be planted, and when it was time to harvest the crops, how the harvest was to be divided, and what part of the harvest was for the poor. But the world has changed. I also want women and young people to be given a place." She laughs: "We no longer want a group of old men making all the decisions."

However, this form of local government takes courage, as Awimbo notes: "The courage to stop complaining, to take your life into your own hands, and to actively contribute to the development of your own neighbourhood, community and country." Awimbo, who lives in the Kenyan port city of Mombasa, supports organisations in Eastern Africa that play a role in local palaver activities. The "Capacity for courage" is what she calls it, the ability to be brave. "I want to strengthen that capacity. This requires people being informed and feeling responsible for making decisions on how they want to live and where." Awimbo is convinced that people want this and, "because they don't lend themselves to pre-programming," the results are impossible to predict.

"We are not as brave as we should be," Awimbo observes. When she says 'we', she means: 'we, Africans'. Too many people prefer hiding behind others because then they don't have to take action themselves. "If you speak with them, they say: 'we don't know because no one tells us'." She also blames those in power, who are interested in keeping others poorly informed. This turns the search for truth into an almost impossible task. "It has everything to do with power and control." Most African politicians and traditional local chiefs don't like sharing information. Officials at the district and central government levels are unwilling (or barely able) to provide information that would enable people to make informed decisions about their own lives. She is not positive about the media either: "We have radio, television and newspapers, but journalists do not provide us with the information necessary to close the gaps in our knowledge." The result, Awimbo believes, is that many people have a distorted world view. "They think it is inevitable that some people dominate others. Or that change is simply impossible."

Acting Based on the Truth

As a result, the problems of our time will continue to fester. "Everyone knows by now that natural recourses are rare. But few people are willing to seek out alternatives. They're afraid that they'll have to change their lives. This also applies to climate change. People deny that it exists because they're afraid of the consequences of recognising this phenomenon. So we need people who are able to accept, and act from, the truth. That is what I mean with 'capacity for courage'. They - and in fact this goes for all of us -must learn to face the truth and act accordingly."

When people have access to better information and are better able to understand how they are being governed, they can respond creatively, suggesting their own ideas instead of simply waiting. "And we should have the courage and determination to demand the same of our brothers and sisters, children, neighbours, friends, and colleagues."

Awimbo's ideal is to have "open days" during which authorities from all levels of government explain what they do, the decisions they make and their performances, and also discuss this with their employers. Awimbo believes this does not necessarily entail, for example, the number of public toilets built, but should focus mainly on informing the citizenry. "In other words: What have the authorities, from a ministry or a municipal government office, done to increase the 'governance literacy' of its citizens?"

Breeding Grounds

Citizens also need to get to work. Awimbo encourages them to express their ideas about how society should be governed, and to test those ideas against the opinions of others. She calls it a breeding ground: where people have the necessary space to safely discuss their ideas. "If you have an idea about your town or your neighbourhood, you need to be able to figure out if it works. Whether it is a good or a bad idea and without automatically having to join a political party. People have to feel that, through negotiation and compromise, they can achieve maybe 70 instead of 100 percent of their wishes, but that, in this way, the other parties will also be satisfied."

Why not leave this task to the politicians? Isn't that why they were elected? Awimbo: "Many people don't understand that the government is there to implement the wishes of the people. They have no idea how they can exercise their influence. We must take responsibility for our own lives. But for the record: the breeding grounds are not there to replace politics, they are there to influence the decision-making processes."

Enhanced governance is not the ultimate goal; Awimbo wants to improve governance over all of the nation's natural resources. "It's our water, our air, our country - what we designate as cropland, what land we need to build houses and businesses, how extensive agricultural production should be. Those kinds of decisions."

Awimbo's ideas stem from her profession as an ecologist; she studies the relationship between plants, animals and humans in an effort to create ecological harmony. This is quite tricky because each of the elements gets in the way of the others. The solution is a compromise in which everyone gives in a little. "I am particularly interested in how ecology affects people's lives."

Awimbo works together with local community organisations to carefully examine how to preserve special natural habitats, without it having an adverse effect on the people who depend on these areas for their livelihood. In other words, with and by these people. "In Africa, nature preserves are often precisely where people live. The worst thing that can happen - and which often indeed does happen! - is that decisions concerning the protection of ecologically important sites are made at the national government level, and thus excludes the people most affected by the decisions. The question thus becomes: for whose benefit are you protecting these areas? The interests of nature obviously do not always coincide with those of the people. So a balance between the two must be found and compromises must be made. A forest where a community harvests honey is essential for the people who live there: it is their traditional way of life. They sell their honey in neighbouring communities. If the forest becomes a totally protected preserve, the local residents can no longer use it to cultivate their honey and they would be prohibited from chopping down trees to create areas for their beehives. Maybe others can do this, but by rigorously protecting the forest from everyone, you also prevent the people who have a vested interest in actually protecting it from having access to it."

'Nairobi Used to Decide Everything'

Top-down decision-making is the normal practice in much of Africa. But Awimbo has observed some changes. Kenya's government is located in Nairobi, the capital, but it is in the process of transferring more and more power to the provinces. "Nairobi used to decide everything. Even the notion of 'local' used to be defined at the central government level. That does not work in a large and diverse country like Kenya. You cannot govern a big city in the same way you do an agrarian community. One perfect solution for all of the different regions is not feasible."

The Kenyan government has established numerous Community Forests Associations together with the local communities in Kenya's swampy coastal region. They give the local people the power to manage and protect their own mangrove forests. They can also analyse whether protection of the natural habitat is possible without adversely affecting local fishing. "This is what we are negotiating now. Twenty years ago, this would have been impossible in Kenya. But after much pressure from the people, it now works. Those in power have always considered the Kenyan people as a source of cheap labour, but never as a part of the decision-making process. That is changing now. That gives me much hope."

What also makes her hopeful is how the mass media in her country are changing. "Fifty years ago, the media were totally controlled by the government and wealthy businessmen. Now anyone can voice his or her opinion. So change is possible."

| Experiencing the beauty of a forest while having dinner Janet Awimbo (1964) has been protecting nature and involving people in this effort for over twenty years. She focuses on educating and training people (capacity building), so that they can better employ their talents and skills to take their lives into their own hands. She also teaches (local) governments how to negotiate with each other and how to reach compromises. She also works on social and environmental justice, including through the Global Greengrants Fund, which she coordinates in Eastern Africa. This fund provides small grants to local groups. "For example, we have given money to a group of people who are protecting a mangrove forest near the coast. They started a restaurant with this money. That attracts people who can experience the value and beauty of the forest." Awimbo has previously worked for organisations such as the Kenya Forestry Research Institute (KEFRI), the World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF), the Impact Alliance, Pact Kenya and the NGO Resource Centre (Zanzibar). She is now a senior consultant with Casework Equatorial, helping individuals and organisations in coastal Kenya become agents of positive change. |

Read more about this subject

-

Blog / 15 April 2024

The year of truth: EU Member States urged to combat deforestation

The EU is the world's largest "importer of deforestation," due to the huge volumes of unsustainably produced soy, timber, palm oil, and other raw materials that EU member states import. After many years of delay, the European Parliament and the European Council passed a law in December 2023 to address this problem: The EU Deforestation Regulation (EUDR). Both ENDS is part of a broad coalition of organizations that have been pushing for this European legislation. However, there is now a serious delay, and perhaps even postponement, of the law's implementation. Objections have been raised by a number of member states, who are sensitive to lobbying by certain business sectors and producer countries.

-

News / 4 April 2024

EU ECA fossil fuel phase-out tracker reveals EU Member States’ lagging commitment to Paris Agreement goals in export credit policies

Our new report titled EU ECA fossil fuel phase-out tracker by Both ENDS, Counter Balance and Oil Change International sheds light on the concerning lack of harmony between EU Member States' export credit climate policies.

The report was updated on April 17th, following new responses by Member States on their respective policies.

-

Blog / 4 April 2024

If we women don't speak up, no one will speak for us

By Maaike Hendriks and Tamara Mohr

By Maaike Hendriks and Tamara MohrThis February women environmental defenders from around the world met each other in Indonesia. All these defenders face structural violence. GAGGA, the Global Alliance for Green and Gender Action, supports these women. This meeting in Indonesia provided a unique space for women, trans-, intersex and non-binary people who are often the subject of conversation but rarely have the opportunity to engage with each other and meet other defenders from around the world. For they are all amazingly knowledgeable, strong and resilient women whom we should take seriously.

-

News / 2 April 2024

The Climate lawsuit against Shell

Milieudefensie (Friends of the Earth Netherlands) and 6 other organisations are confidently heading into Shell’s appeal of the 2021 climate ruling, which will take place on April 2nd in The Hague. In the landmark lawsuit against the oil and gas company, the court decided that Shell must slash its CO2 emissions by 45%, in line with international climate agreements.

-

News / 29 March 2024

Both ENDS visit Tweede Kamer to talk about destructiveness of dredging worldwide

This week several Both ENDS colleagues visit Tweede Kamer der Staten-Generaal to meet Christine Teunissen and Luc Stultiens with partners from Mozambique, Indonesia and the Filippines to talk about the destructiveness of dredging worldwide and especially in projects with the aid of the Dutch government.

Read their plea

-

News / 27 March 2024

Changing of the guard: Paul Engel and Leida Rijnhout on the unique strength of Both ENDS

After eight years as chair of the Both ENDS Board, Paul Engel is now passing on the baton to Leida Rijnhout. In thus double interview, we look back and forwards with the outgoing and incoming chairs. Paul Engel sets the ball rolling on an enthusiastic note: “This organization decides itself what it is going to do, and does it very well. As the Board, we help and use our networks to provide support”. A conversation about taking the lead in systemic change and working with others around the world.

-

Press release / 25 March 2024

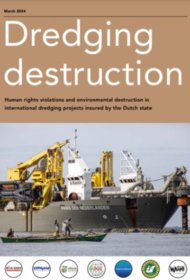

Dredging destruction; worldwide research into Dutch dredgers

Dredging Destruction: Report reveals how Dutch dredging companies are systematically destroying human lives and the environment around the world with the help of taxpayers’ money

The Netherlands is providing billions of euros in support for dredging projects by Boskalis and Van Oord around the world. All of these projects are destroying human lives and the environment. The Dutch government’s policy to protect people and planet is failing systemically. And after twelve years of studies and talking, there are no real improvements. It is time for a thorough clean-up of government support for the dredging sector.

-

Publication / 25 March 2024

-

News / 19 March 2024

Both ENDS - Remarkably Special

At Both ENDS, we hold our own responsibility, self-direction, an open feedback culture, and personal development in high regard. Chaos, you might think? Not at all, it leads to an effective way of working with much enjoyment. The flat organizational structure that Both ENDS has been implementing since 2016 is founded on collectivity. In this, you can also see our aim of 'Connecting people for change' reflected.

-

News / 12 March 2024

Equality as a key for international trade

Trade has been in the global spotlight once again in recent times. Recently, ministers from around the world gathered in Abu Dhabi at the WTO for negotiations on world trade in the coming years. However, participants from civil society were silenced. Never before has their freedom been so severely restricted at the WTO. In a time when geopolitical tensions are escalating by the day, it is crucial to prioritize equality in international trade. -

Event / 12 March 2024

From Policy To Practice: Funding Locally-led Gender-Just Climate Action

A discussion on the intersection of climate and gender justice - specifically on financing mechanisms for gender-just climate solutions!

-

News / 6 March 2024

Inspire inclusion at Women's day!

Happy Women's Day!

Friday March 8th we celebrate a gender equal world; free of stereotypes, bias, and discrimination. Around the world women are powers of change. We proudly present you; the voices of the next generation of environmental leaders of the JWH initiative. All our grantees are driving change in the environmental sector and have a strong say about the inclusive world.

-

News / 6 March 2024

Export Credit Agencies and development finance in the EU

We are seeing increased interest in the EU for blending different development financial instruments with export credits, even though export credits are not fit for this purpose. The European Commission is developing plans for using so-called export credits for financing everything from raw materials, to development projects, to weapons. A new report of Counter Balance is shedding light on the significant environmental and social impacts of projects financed by ECAs.

-

Press release / 4 March 2024

Dutch government calls for investigation into Malaysian timber certification

The Dutch government expects PEFC International to undertake an investigation into its own role as a forest certification system, using the Malaysian Timber Certification Scheme (MTCS). "It is about time the Dutch government takes a leading role in ensuring Malaysian timber entering The Netherlands is not associated with deforestation and human rights abuses," states Paul Wolvekamp of Both ENDS. "Considering that the Dutch government has the ambition to build 900.000 houses in the immediate future, involving massive volumes of timber, such as timber from Malaysia for window frames, builders, contractors, timber merchants and local governments rely on the Dutch government to have its, mandatory, timber procurement better organised, i.e. from reliable, accountable sources'.

-

Blog / 27 February 2024

Partners fighting for rights within natural resource exploration in Uganda

A recent visit to Uganda highlighted the country as the latest example of ethical, environmental and human rights dilemmas brought forth by natural resource exploration.

Under the guise of economic prosperity and energy security, the future of Uganda’s forests, lakes, national parks, and by extension that of the people that depend on these resources, is increasingly endangered. Both ENDS partners in Uganda work with local communities to preserve these natural environments and the livelihoods that come from it.

-

Blog / 26 February 2024

Brumadinho: 5 years without justice

On January 25, 2019, Brumadinho region witnessed a tragedy-crime that claimed 272 lives, including two unborn children, affectionately called "Jewels" in response to VALE’s declarations that the company, as a Brazilian jewel, should not be condemned for an accident. However, the investigations about B1 dam collapse, at Córrego do Feijão Mine, showed that the scar left on the community and environment was not an accident, but VALE negligence.

-

Blog / 26 February 2024

Exploring sustainable farming practices with partners in Indonesia

From land regeneration to improving soil health – trees play a crucial role in almost all our ecosystems. Agroforestry makes use of these benefits by combining agriculture and forestry. Agroforestry, and the reforestation and conservation efforts that are part of it, improves biodiversity and climate resilience, as well as the livelihoods of the farming communities involved.

-

Blog / 26 February 2024

Impacts of the fossil fuel sector in Guanabara Bay

Last September, together with our Brazilian partner FASE, Marius Troost of Both ENDS visited Guanabara Bay (near Rio de Janeiro) to map the impacts of the fossil fuel sector there. During the trip, he was struck by the braveness and fearlessness of the local fisherfolk who protest the injustices faced by the people who live around Guanabara Bay and about the damage done to the environment.

-

News / 14 February 2024

Petition to protect the Saamaka people and the Amazon Forest

The Saamaka People, the Afro-descendant tribe of Suriname, have preserved close to 1.4 million hectares of the Amazon rainforest. They have for decades urged the government to recognise their ancestral territorial land rights.

-

News / 8 February 2024

The litmus test for the devastating race track in Lombok

A race track for international motor bike events in Lombok continues to worry human rights experts around the world. Both ENDS and its partners are increasingly concerned about the project’s implications for ethical standards in global development financing going forward for it continues to hurt the most basic social and environmental safeguards.